Payments are complex. It's one of those technology layers we use multiple times a day and it just works, and we never give it a second thought. But behind each tap, swipe or digital flow is a myriad of technology providers, fiercely competitive companies, some of the world’s most powerful network effects and a whole lot of regulations and geographic diversity.

I first started exploring the payments space as a Toast investor and went much deeper while looking into dLocal, a payment processor in emerging markets. That’s led me down the rabbit hole as I found a space rich in interesting history, technological shifts and true strategy business dilemmas.

My goal in this overview of the payments landscape is to provide a framework for evaluating the many companies in the space. To do that I’ll:

Break apart and explain the components of the payments industry: briefly explain how we got to where we are and the different aspects and players: what payments actually IS, the shifts to credit/debit cards and from there to e-commerce and omni channel.

Explore the key dynamics that impact companies in the space: competition, scale economies, technology trends

Provide a framework for evaluating companies in the payments space

A lot of research has gone into this writeup, including researching many companies in the space (Stripe, Adyen, PayPal, Shift4, dLocal, XYZ, Toast, Litespeed, JPM, Fiserv, Global Payments, FIS, Riskified, Payoneer, and Remitly) as well as some great substacks I highly recommend: Bob’s payments substack, Payment’s in full, Popular fintech and Payment’s strategy breakdown.

It's been a pleasure learning about a space I never knew. Investing is a great hobby 🙂 Now, let's dive in!

P.S if you know a lot about payments some of the below might be obvious, but I'd encourage you to read as their are some less known nuggets that I've uncovered.

Some payment history and context

We don't appreciate cash enough. It's a wonderful innovation that's taken years to come together in its present form. What's so amazing about today's cash, is that it is its own ledger. No one needs to keep track of it on some database. When a consumer gives it to a merchant, they're immediately debited and the merchant receiving the cash is immediately credited. That's it. There are no merchant questions of 'will the consumer cheat me of my money?' or consumer questions of 'will I ever receive what I paid for?'.

That isn't to say there's no concern of fraud. There are still things that need to verified: that the cash is not forged, and that the giver is not being coerced.

When payments went to a non cash based system (both physically on location and digital where there's no card present) these issues became more complex due to the lack of a unified ledger. There's no cash operating as the unified ledger that everyone trusts.

Non cash payments still need to verify:

The authority of a transaction (that a consumer isn't being 'coerced' and has the authority to transact)

That the transaction is legitimate and not forged in some way

But in addition non cash payments now needed to verify new things:

That a customer has the funds to pay! In cash this was easy, but in a no cash world someone has to check that the consumer has the funds to transfer.

That funds can and will transfer to the merchants bank account

That all the information that's being processed and transferred to perform the above two tasks is done securely.

It's the above three points that credit card payment networks like Visa and Mastercard do. They connect your merchant to the consumers bank account, verifying the right to transact, the funds to do so and make sure the funds settle, while ensuring information security along the way. In return for this work credit card networks take a fee of the processed money.

To ensure all of the above requires several different actors and jobs that need to be done. This is a lot of work for one company, so the two dominant credit card networks, Visa and Mastercard outsourced this work in return for a portion of the fee they take to process transactions. American Express on the other hand does all the consumer issuing and merchant acquiring on their own.

Merchant acquirers: As the name suggests, these financial institutions acquire merchants and act as the middleman that connects them with the credit card companies.

Issuing banks: Consumers receive credit card from someone, right? This usually is a bank or some other financial institution that acquires customers and issues them a credit card - think a Chase Visa card or Costco's Visa card. Acquiring customers is a costly act and that's why the acquiring actor receives the lions share of the payment processing fee.

Hardware providers: Credit cards need to work with on location hardware. These companies work with the credit card networks and the merchant acquirers to develop and distribute the relevant hardware to shops so that you can swipe, tap or NFC your payment.

Payment Processors: If a merchant only offers one payment option, like Visa, things stay relatively simple - a merchant can use a hardware device that connects directly to the Visa network. But what if they want to offer other payment methods like other credit card networks, for example Mastercard or American Express, or other payment methods entirely, like Venmo? For that they need a payment processor, someone who knows how to accept different types of payments and route them to their appropriate network.

Fees were split between the different actors in the network based on the task, type of payment and many other vectors.

When payments were primarily 'on location', i.e at a store, there was a lot of overlap between the hardware vendors, the payment processors, and often enough the merchant acquirers. In store payments gave rise to a few industry needs like fast processing time, imagine if it took a few minutes for a transaction to clear while you're standing at the supermarket, as well as specific security regimes, like pin codes or signatures. Lisa Ellis of MoffetNathanson had a great interview on Stratechery where some of this is discussed:

Lisa Ellis: …In-store payments is remarkable technology, honestly, because the throughput requirements are so high, everyone gets impatient if they’re standing at the checkout register at Target and it takes more than about 20 milliseconds for your card to authorize and so you just imagine those are millions and millions of capillaries coming off of every cash register, funneling back to these gigantic data centers that are processing all these payments, 24/7/365, with huge walls of fraud protection around them. There’s all these latency issues, you have to be physically close to the stores when you’re doing that.

You might be less familiar with the companies who facilitate these kind of transactions: Fiserv, Worldpay, Global Payments, Fidelity National Information Services (FIS), JPM Payments and more. Indeed, the fact that so many people don't know about the pipes that power the payments system that moves trillions of dollars speaks to a main aspect of the payments industry - it's been obfuscated away.

The merchant acquiring industry for on location PoS has been commoditized for over a decade, at least in developed markets. As the market matured, technology standards coalesced around the two incredibly dominant credit card networks that are accepted basically everywhere, Visa and Mastercard, and the information standards that ensure the reliability and security needed for the amount of PoS transactions. Transaction acceptance rates are high, at 96% of on location payments approved and all the infrastructure built out.

Commoditization led to consolidation among the large acquirers to achieve the economies of scale that underly the payments processing industry: with the same infrastructure processing additional transactions is net margin accretive, even if the marginal transaction comes at a very low profit margin.

However all this changed when two things happened, and true disruption hit the payment processing and merchant acquiring market. The first was the emergence of online payments. To quote the continuation of the same Lisa Ellis interview:

But all of that, from a network architecture, is designed around an in-store footprint. So the minute you’ve moved to online payments and all of a sudden it’s just one big data center where you’ve got one big website, but the complexity is more about things like authorization, because God knows where the customer is coming from, and it’s much more algorithmic.

E-commerce brought a host of new customer needs and ‘jobs to be done’ by payment processors. The incumbents weren’t the natural best fit for this, and in fact one of the first dot.com darlings, PayPal was founded on solving e-commerce payments, more on this below.

The second foundational shift was the built on a greater technology trend of the ‘consumerisation of business software’, where business owners expected their business software to be as smooth, easy and quick as their consumer apps and products. Square built on this new need, combining software + hardware to meet growing needs in a mature, stagnant market that no longer served the small merchants. They innovated on merchant acquiring across axis that hadn’t changed in years in five areas:

Hardware: A simple cheap dongle now enabled payments, instead of a legacy system. The dongle plugged into an iPad, which was quickly becoming a store management tool. Using an iPad with paired Software enabled easy updating over their store management software.

Software: Square was the first to offer an integrated HW/SW solution for small merchants to run their stores. loaded their service with free, basic software that helped a small merchant manage their business. This was the beginning of the vertical SaaS era for payments.

Pricing: Instead of obscure fees based on interchange and qualifying and non qualifying credit cards that most merchants didn’t even understand, Square used a simple pricing model that was clear and intuitive for merchants.

Distribution: Instead of selling through banking partners or 3rd parties, Square sold directly to merchants using a self-service model. The dongle was available at retail locations (or online) and since the pricing and value offering was clear, merchants were ripe for the model.

Embedded finance: After the initial success of Square’s model they started offering additional financial products to small merchants, like Square capital - easy lending to SMBs, who prior to this had no alternative but bank lending, which might be to onerous or non user friendly.

Square essentially embedded payments and the acquiring side of things into an overall value proposition that until now had all been disparate pieces.

These two shifts, the rise of e-commerce and embedded finance are the two underlying shifts of the industry over the past decade.

Online payments

Online payments completely changed the game for merchants in many ways. Merchants now had to digitally integrate payments into their websites, (in additional to building a website, something that was new to them in the first place). E-commerce introduced new challenges. The first was bridging the trust between merchants and consumers - that payments would be paid and products received. Other new requirements were security to protect credit card information (I won’t go into the early days of the internet where the idea of inputting credit card information online was unthinkable). Merchants needed to accept cards from anywhere in the world - cross border commerce. Over time this would morph into not only accepting an international Visa or Mastercard credit card but also alternative payment methods (APMs). The nature of fraud and chargebacks also changed. Consumers aren't inputting their pin or signing a transaction and merchants had no way to know if a customer actually bought something or was defrauded with a stolen credit card.

If fighting fraud sounds as far fetched to you as it did to me in the beginning, apparently this is one of the industry's never ending battles for the internet economy. As Stripe's 2024 annual letter describes:

Fraud is a bigger drag on the global economy than you might think: one report found that fraud cost 3% of a typical online business’s revenue. Fraudulent actors today operate on an industrial scale, with teams of engineers, managers, and data analysts.

That's 3% of revenue, not profit.

To add to this, new payment expectations and business models popped up: subscriptions, micro transactions, buy now pay later were all new forms of payments that required more sophisticated payment processing. This complexity has only increased as new forms of payment options have emerged: digital wallets, prepaid cards, local regional cards, bank transfers, ACH and a variety of mobile wallets like Apple Pay or GPay, and cryptocurrency. When you go global, the complexity increases by an order of magnitude. dLocal, a payment processing company that covers 40 emerging markets offers online merchants 900+ payment methods.

Here are just a few examples of payment rails and methods in different countries beyond your traditional credit cards:

India: Adhaar, Paytm

Brazil: Mercado Pago, Pix

US: Venmo, Cash app, Zelle

Mexico: Mercado Pago, BBVA app

Argentina: Mercado Pago, Uala

Sweden: Swish

Germany: Paypal

Kenya: M-Pesa, Airtel Money

Indonesia: GoPay, OVO

Nigeria: Opay, Palmpay

What all of this means practically speaking for the payments business is that if once upon a time a merchant could be happy with a hardware terminal with a hook up to a payment company that took care of everything, today the landscape is more complicated.

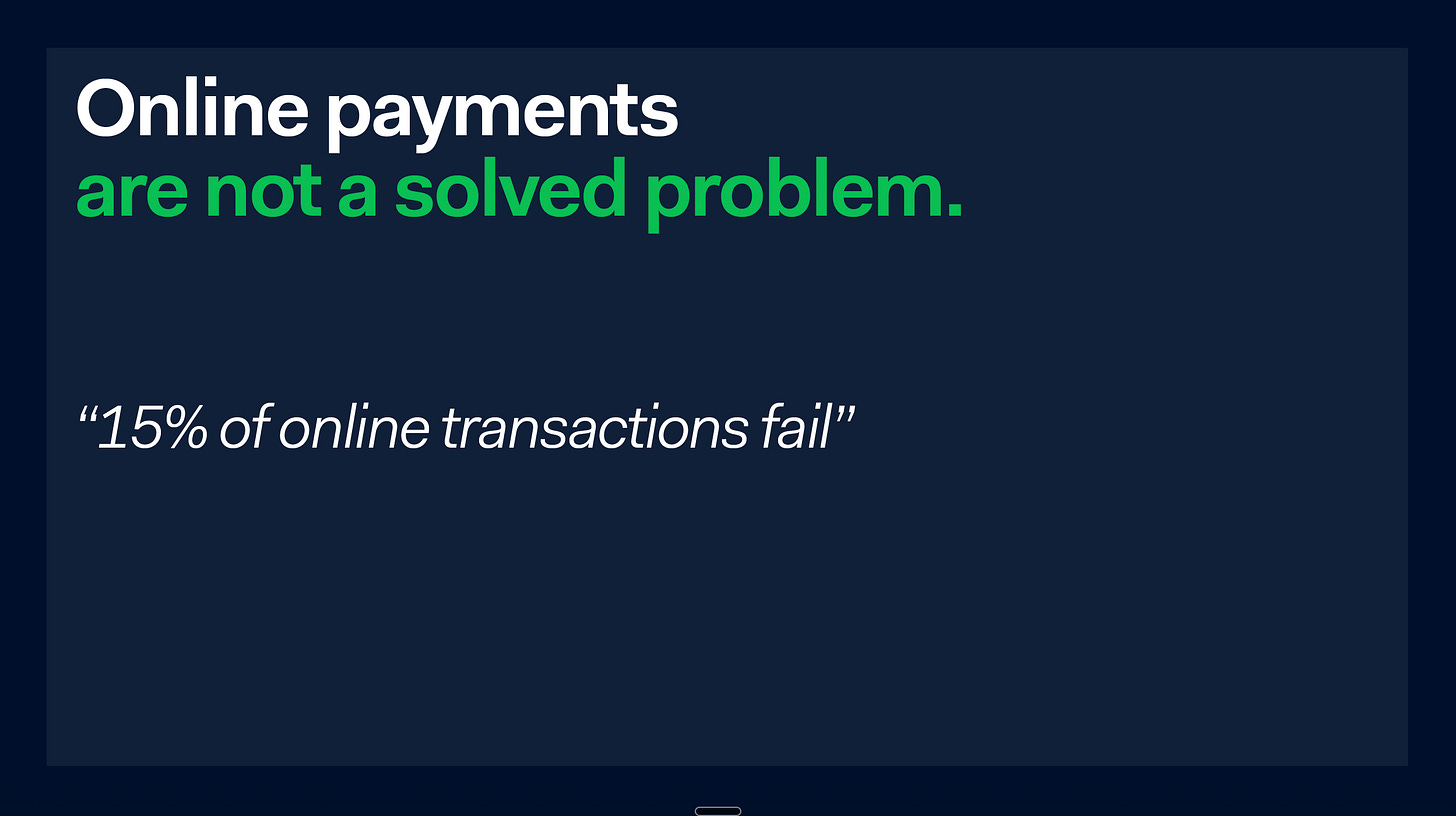

Merchants now need to work with a payment gateway and payment processors to deal with the variety of issues they'll encounter. And it's worth the investment. A merchant that sells online and spends $75 to acquire a customer and bring them all the way to their checkout page doesn't want to lose that sale because they don't offer a convenient method of payment, or that a declined credit card transaction. These rejections happen more often than you think, according to Adyen, a leading global payments provider, digital transactions fail 15% of the time, compared to only 4% for card present transactions.

To summarize, the shift to online payments meant that there was a whole host of new problems to solve across the payments space:

Increasing the number of payment methods they accept

Increasing the currencies they work with

Global expansion: Local vs international merchant acquiring (this will receive a separate section below)

Security

Billing and subscription management

Integration ease

Analytics

Conversion rate and fee structure

Regulatory compliance

Omni channel and global footprints

To add to the complexity are two unique challenges. What if a customer buys online and wants to return in store, but the payment has been managed by two separate retail organizations within the same company? What if they've used different payment flows and have no way to track that payment? The rise of omni channel, especially during Covid-19, when buy online and pick up curb side at retail locations became very popular forced many retailers to evaluate how they view their entire database schemas and their payment flow in particular. Managing two different flows made refunds, charge backs and generating a holistic view of their customer a challenge. This added a unique selling point to payment processors who could bridge the two formats, not an easy feat! Online payment processors had to integrate or build their own hardware terminals, and distribute them, as well as deal with retail transaction volume, which as Ellis points out above is very different from online transaction volume.

On the other side, payment processors who had built out their entire technology stack to deal retail store volume would have to build out payment gateways and processing integration, deal with fraud and analytics and specialize in new geographies. Not many payment processors managed to bridge the gap.

Those who could however, generate a lot of value for their merchants and in turn, themselves. Adyen is one of the few and they've built a whole 'Unified Commerce' offering around it:

Geographic expansion

Another complexity worth dedicating its own section to, despite being mentioned previously, is geographic expansion. While Visa and Mastercard are now global payment options, that's a far cry from saying that a merchant can get away without local payment options. Even in developed markets like the EU and US adopting to local market conditions are needed. This isn't only across payment methods, but also from a regulatory perspective, currency pairs, pay in and pay out regulations and tax withholding.

Emerging markets such as LATAM, South east Asia and Africa are an even more complicated picture.

Credit cards are used but are nowhere near as dominant as they are in the developed world. Whereas in the US or EU a merchant can serve 90% of their market by only accepting credit cards, in emerging markets this isn't the case. Each country has a variety of different payment methods that are just as popular if not more. These include prepaid cards, digital wallets (that are not Apple or Google Pay), mobile wallets (for example Pix in Brazil and M-Pesa in Kenya), or different payment rails entirely, such as UPI in India. Not accepting local payment methods leads to lower conversion rates and many customers not even able to purchase. Important to note that different payment methods have different fraud rates and analytics required.

Approval rates for local cards used in online purchases can jump from just 20–45% with traditional offshore methods to 80% or more when using local acquiring solutions. - Rapyd data

Volatile currencies and foreign exchange challenges. Emerging market currencies fluctuate dramatically and occasionally suffer dramatic devaluations or repatriation denials. This requires companies to become risk managers, not part of their core business.

Different regulatory structures and requirements than in developed markets, and often completely different regulatory approaches.

Smaller markets than the US, EU or even specific countries or states in those regions. Emerging markets by nature have smaller, less developed economies and therefore often don't merit the same direct investment that a larger market might.

A way to mitigate this is by working with a payment processor who has local connections or by going direct with local acquiring, which has several benefits, mainly that it's cheaper, provides a higher acceptance rate of payment methods and complies with local regulation. However these benefits come with challenges, mainly the need to be able to operate a financial entity in different emerging countries, deal with foreign exchange and the potential currency fluctuations and regulations, and maintaining these entities. Stripe has a good blog post on local acquiring.

Summarizing the state of the payments industry

At it's core, payments is a networking, messaging and regulatory solution. It requires:

Being recognized, connected and the ability to message with payment networks and local and international banks and other financial institutions.

Complying with local regulation: payment processors and money transmitters must file in different countries and states with different regulatory bodies and comply with different regulations and reporting regimes.

Doing it well in a complex, digital and omni channel environment involves specializing in many areas, such as fraud and acceptance rates, local acquiring, ease of integration and ramp.

Part of this stack is completely commoditized and part of it isn't. The next part of this article will translate the above overview and history into industry dynamics and the rise and decline of specific companies.

Industry dynamics, new players, new competition

After understanding the basics of payment let’s explore the industry dynamics that have been playing out:

Secular growth

Mission critical

Increased competition

Fintech Innovation:

Building on credit cards

Building new rails

Tools for e-commerce

Embedded finance

Scale scale scale

Ways to scale:

M&A

Vertical integration

Geographic horizontal approach

Secular growth

The first and key driver of the entire industry that can't be underestimated or forgotten is that payments has been an industry in secular growth. The global shift from cash to credit cards and then to other forms of digital payments, whether in store or online has been massive, long and is still in the process. This tailwind has enabled all of the companies in the space to grow for decades, despite increasing competition and commoditization of the technology.

Only recently has it come under pressure in the legacy players as new entrants outcompete on new value propositions.

The secular growth of the industry has hidden a lot of shortcomings in specific players: legacy technology, bad M&A and consolidation. As new markets needs have emerged the leaders and the laggards have been split apart.

Mission critical offering

Processing payments is mission critical. Without taking a custoers money, there IS no business. However it's not the part of the business that is usually associated with acquiring new customers or growth. It's a boring, mission critical, part of the company that should just work. In the past, enabling payments meant high barriers to entry: a merchant needed hardware terminals, dedicated connectivity, and a contract with an acquiring bank or financial institution to access networks like Visa/Mastercard.

Payment companies themselves had to invest heavily in data centers and proprietary networks to ensure reliability and the functionality of this mission critical software. Because hardware was involved, if the hardware was good enough, as a merchant you'd have one payment provider. It didn't make sense to work with several.

As the payment infrastructure matured and become more commonplace, the technology layer matured, standardized and as a result - commoditized. PoS hardware terminals became similar. Fee structures consolidated around Visa and Mastercard fees. Innovation stagnated and merchants couldn't really care who they worked with as long as payments worked.

This changed over the last decade, while the core mission criticality hasn't changed, the infrastructure has modernized dramatically because of the shift to online payments. Payments are still critical infrastructure (every online store or point-of-sale depends on it), but they've become much easier to integrate. When no hardware terminal is required, and cloud-based processing and APIs exist, payment facilitators now let businesses integrate payment services with far less friction. For example, a small online seller can start accepting cards within minutes using Stripe’s APIs – a far cry from the old days of lengthy bank merchant account applications. Additionally, in online only businesses, when there's no need for dedicated hardware, companies can build their own payments stack relatively simply and cut out the middleman if it's worth the effort.

This has led to increasing competition on the core payment processing and the inevitable drop in take rates.

Increased competition

Because of how mission critical it is, when it comes to larger merchants, they work with several payment processors in parallel. A large merchant, like Facebook, Uber or Airbnb, might have their own in house payment stack as well as work with one or two other payment processors simultaneously. They can never afford to have their payments down and so if one stack has an error, they'll immediately shift to the provider that's still up and running. power

For investors this means that a PSP can be losing market share without losing logos.

This dynamic is incredibly impactful to the payments industry. It means that switching between payment providers is almost as easy as 'turning a dial'. Here are three examples from recent history, the first is from the aforementioned discussion between Lisa Ellis and Ben Thompson on Stratechery discussing how Adyen got hit by lower volumes during 2023 and the second is dLocal losing payment volume in Q1 2025, and last from PayPal:

Lisa Ellis: these big merchant platforms are — who by the way, always have more than one acquirer hooked up to them because they need that for business resiliency reasons in case one goes down for some reason. So there’s always at least two options.

Ben Thompson: So it’s just turning a dial. Like, “Do I run more through Braintree or more through Adyen?”

LE: Yeah, I mean, it’s marginally more difficult than that, but not too much more difficult than that, which is because you might have —

Ben Thompson: (laughing) It’s not a literal dial.LE: You might have 80% here, 20% there, or you might even in the market, the scale of the US have three, and you’re sort of turning, adjusting across those. So it can happen quickly.

dLocal Q1 2025 call:

Pedro Arnt: The quarter-over-quarter comparison is explained by the commerce performance in Mexico, given the seasonality effect in the fourth quarter and partial loss of share of wallet with a large merchant......

Pedro Arnt: Mexico when we refer to share of wallet losses, by definition, it means it's going to someone else.I think that's the nature of this business.

What makes things more complex is the coopetition that exists: some companies might compete head to head with each other and yet still work together.

And from PayPal’s CEO at a 2025 industry conference:

Because most large enterprises are using multiple processors to be able to manage their processing, they need to make sure that our Fastlane experience works through not just Braintree, but also other processors. That's why when we launched, we had other processors, including competitors. So we had Adyen, Chase and Fiserv and others adopt and market our Fastlane product.

It’s an incestuous business!

The same is true for Paypal's payment orchestration product, which competes head to head with Adyen, yet also offers an orchestration product that determines which payment processor is most likely to have the highest acceptance rate and could route via Adyen.

So while payments are mission critical, because the core payments layer has been commoditized, merchants who sell online will work with several in parallel, making the competition fierce, and driving fees lower and lower.

When take rates drop, how do established companies expect to grow in this competitive environment? By takings share.

From Adyen’s Investor presentation, their growth algorithm’s biggest contributor is low double digit to mid teens growth from ‘share of wallet gains’ - i.e taking share from other payment processors.

This dynamic only becomes more present in a global world where a large merchant will be working with multiple payment processors across different geographies and the competition on fees and acceptance rates is fierce (more on this below). Spotify for example works with Adyen in Europe but has also been working with dLocal in LATAM and Africa. It's not hard to imagine that Spotify will also work with Adyen in Brazil, a market that dLocal has lots of expertise in.

For investors this means that Payment service providers can be losing market share without losing logos.

A new era of fintech Innovation

E-commerce brought a host of new customer needs and ‘jobs to be done’ by payment processors. The incumbents weren’t the natural best fit for this. Additionally the trend of consumer expectations meeting business applications led to a new wave of entrepreneurs who wanted to simplify, speed up ad reduce fees even further in the payments space. The 2010’s with the rise of the cloud, mobile and social technologies were the right time to improve the process, both online and at the terminals.

This led to a few key innovations vectors in the payments space:

Building a better experience on top of credit cards:

Replacing credit cards

Innovating on the e-commerce payments flow and

Bundling of payments into other software offerings

For example Square innovated on vectors #1 & #4: their new hardware and software integrated PoS was built on top of the credit card system.

Let’s explore each of these innovations.

Building on top of credit cards

If you're building on top of credit card infrastructure it's very hard to generate good margins, Ben Thompson explains in a 2014 article on Square:

The challenge here is that margins are incredibly tight. Consider a $50 transaction paid for with a Visa card swiped through a Square reader:

The interchange fee (which goes to the card-issuing bank) for swiped Visa cards is 1.51% + $0.10, which in this example is $0.855

Various assessment charges (where Visa actually makes its money) come to ~.11% + $.03, which in this example is $0.085

Square charges merchants 2.75% for swiped cards, which in this example is $1.375

Square’s final takeaway is at most $0.435.

Were the card issued by American Express, Square would actually lose money (assuming a $1.75 fee from a 3.50% discount rate).

Those aren’t great margins, to state the obvious.

The only way to reach profitability with margins like this are scale. If you reach the necessary scale lots of benefits accrue as a payment provider: you can negotiate lower costs with credit card networks, you can net out transactions on your own balance without needing to pay other networks, you can net out foreign exchange, you spread more revenue across the same fixed cost.

Replacing credit cards

While innovating payments in developed economies is tougher due to the cost structure, replacing credit cards was a challenge due to the powerful network effects that payment networks have. PayPal was one of the early innovators here, and with its acquisition of Venmo, one of the only successful companies in developed economies to succeed.

The case is quite different in emerging economies where credit card networks were never nearly as dominant and the jump to mobile leapfrogged credit cards. This meant that digital wallets, paying with QR codes or NFC became second nature, much faster than swiping a credit card. Many emerging economies saw a rise of digital payment alternatives, such as WeChat Pay and Mercado Pago, that were built off of the classical credit card network rails (I listed quite a few above). Central banks also had a role here with digital banking payment rails like UPI in India. Last but not least are stablecoins that also offer an alternative payment rail to the credit card networks.

Innovating on the e-commerce stack

Selling online offered a whole set of challenges for merchants:

Increasing the number of payment methods they accept

Increasing the currencies they work with

Global expansion: Local vs international merchant acquiring

Security

Billing and subscription management

Integration ease

Analytics

Conversion rate and fee structure

Regulatory compliance

Innovating around these issues has given rise to very successful companies in this space in just the past decade that have out competed legacy solutions:

Stripe solved for being developer friendly, fast to integrate and simple, which helped them win massively in online businesses, processing $1.4 trillion in TPV in 2024.

Adyen solved helping enterprise customers sell into multiple markets in the EU, each with its own challenges and pain points. This increased conversion rates, opened new markets and improved the developer experience for Adyen's customers. Adyen processed $1.3 trillion in TPV in 2024.

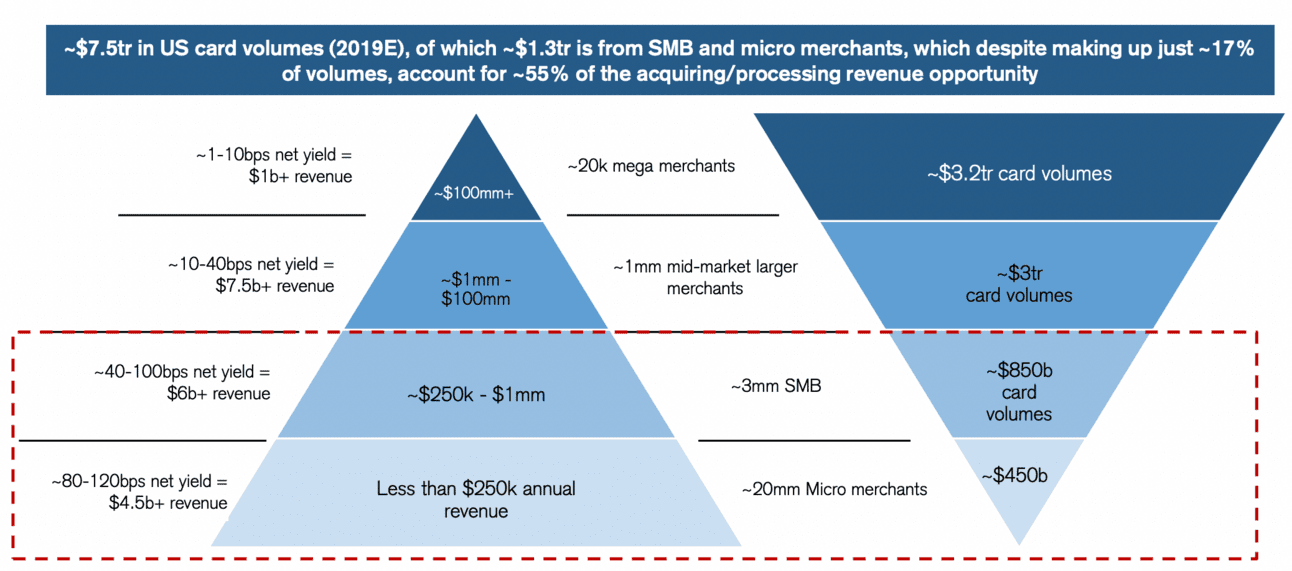

Both go to markets (top down and bottoms up) are valid options based on the 'payments pyramid', from Credit Suisse:

As online commerce and the internet economy grow new complexities and opportunities emerge. Marketplaces across the world need to collect and distribute payments globally. Airbnb needs to collect from a guest from Norway and pay a host in Kenya, Uber needs a similar flow as well as to collect and pay locally across the world, while providing drivers the necessary documentation for regulatory filings. Deel facilitates a global workforce. Subscription and SaaS services can earn or lose money based on customers churning due to failed payment methods.

Global e-commerce comes with it’s own unique set of problems which I mentioned previously, so while Adyen is a great solution in Europe and other markets, it might not be the best processor for Nigeria or Egypt, in which case a new company would need to service that.

Embedded finance

Dwayne Gefferies, author of Payments Strategy Breakdown has a good phrasing for what the embedding of finance is and means:

For decades, payments were always treated as a separate layer in commerce, with merchants selecting acquirers, PSPs, and gateways to handle transactions. That’s no longer the case.

Today, payments are becoming infrastructure, running in the background of software platforms. Instead of merchants choosing a PSP, the software they already use, whether it’s an e-commerce platform, a marketplace, or a SaaS tool, is bundling payments into the experience.

This changes everything.

This means software companies, not traditional PSPs, own the payments relationship.

This also means that payment processing is no longer a standalone business but a feature within a broader ecosystem. If this trend continues, payments will become increasingly invisible over time, turning from a competitive advantage into a utility.

Embedding payments into SaaS and offering the entire bundle to merchants was one of Square’s original key innovations. No small restaurant owner really cares about the payments stack - they care about an overall software solution that helps them run their restaurant better. Vertical SaaS is the solution and many companies now exist in the space, from Toast and Slice in restaurants to gym and yoga platforms.

It’s not just limited to vertical SaaS. Any company that aims to service merchants or businesses of some sort think Shopify, Uber, Airbnb, need some payments or fintech offering. Becoming a payments platform for other platforms is a key strategy to both Stripe, Adyen and other payments processors.

From Stripe's 2024 annual letter:

These platforms and more than 14,000 others use Stripe to offer payments services to their customers. And across nearly every sector of the economy, we see more and more independent businesses leveraging software platforms for impressive growth.

Scale Scale Scale

Payment processing is a great business. It's a toll road in a secular growth industry. There’s great operating leverage as additional transactions are spread over the same technology stack. However, all of this holds true only when scale is achieved. In payments, bigger is better.

Scale brings tangible benefits: lower average costs to transact, broader networks, and more data to ensure both less fraud and higher acceptance rates. Many costs in payments (like building a global network or complying with regulations in dozens of countries) are fixed – so a higher volume of transactions spreads those costs and boosts margins. Scale also confers bargaining power (to negotiate better rates from banks or card schemes).

It’s not only about the cost structure, it’s also about the ability to innovate. Companies like Stripe and Adyen are attractive to merchants because their GMV scale supports deeper R&D investment than any merchant could afford alone. They can amortize development costs across many clients and high TPV, resulting in a product that typically outperforms what a single merchant could build—even if that merchant became their own processor to lower fees.

From a Stratechery interview with Stripe's co founder, Patrick Collison:

Ben Thompson: Why would an established company use Stripe instead of simply getting a merchant account and saving money on fees?

Patrick Collison: It depends on the nature of the business of course, just as it does with AWS. There are all kinds of additional products or services or things that businesses need that can become difficult or impossible to build themselves. So whether it’s better fraud prevention or supporting payments mechanisms that might be very important but that they themselves might not be able to support, like SEPA in Europe, or ACH, or Alipay, or whether it’s running a marketplace through Connect or sort of having Stripe handling all the subscriptions billing infrastructure, and so forth. You’re going to kind of see more of these over time.A good example of this is if you compare, Lyft uses Stripe while Uber does not; they launched before Stripe existed [Editor: Uber uses Braintree]. And if you compare the size of the Lyft and Uber payment teams and you look at how much infrastructure Uber has had to build compared to how much we’ve been able to handle in contrast for Lyft, and how much Lyft has been able to take advantage of the economy of scale in everything we’ve been able to build for the platform as a whole, it’s a big difference.

.....

For example, Lyft now does instant debit card payouts to their drivers, so at the end of Friday night after driving you can just tap “Cash Out” in the app and you just now have your earnings right there in your bank account, whereas with Uber you need to wait until the next week; for many people this is a big deal. If Lyft had to be going and building all the necessary bank integrations and back-end systems and so forth required to build a product like that something has gone wrong. Lyft’s comparative advantage is not figuring out how to implement instant debit card payouts. But because they’re built with Stripe they can in the most straightforward way take advantage of that. So that’s the sort of dynamic that we see play out.

Stripe, by virtue of servicing many customers and a higher GMV, can afford to invest more in R&D and product development than Uber, the largest ride hailing service in the world. This offers Lyft, with a much smaller team to have a better overall payments processing experience.

Scale brings benefits both on the cost and on the revenue side. It’s the holy grail of payments. In the charts below I compare GMV vs operating margin from some of the disruptors below. They all exhibit a march from the bottom left to the upper right as GMV grows.

While Remitly isn’t a payment processor per se, they operate in the same business - transmitting money from place to place and the same dynamics play out.

For Toast I brought metrics only for the payments segment of GMV vs the segments gross profit margin. Barring Covid we see a rising gross profit margin as scale increases.

Adyen and dLocal, both pure payment processors each tell a different individual story. dLocal, unlike many early stage companies is actually profitable, with a positive operating margin on much lower TPV volume than other companies in the space. However they’ve experienced a decline in operating margin as they’ve grown. What’s going on? If we separate COGS (which is payment processing fees they pay to their partner banks and financial institutions) from the rest of operating expenses we can see the same story. COGS growth have seen a dramatic decrease as TPV has grown, meaning the company is finally achieving scale and leverage on COGS - they’re able to negotiate better fees from partners and route through more efficient paths. Operating margin has decreased because, ironically, the company hasn’t yet achieved the scale they need to exhibit the scale economies over the entire company - R&D and S&M included. As they grow their TPV further they’ll start to accrue the benefits of scale on operating margin as well.

Adyen is the poster child of the payments industry. They’ve grown incredibly quickly over the past decade and have reached real scale, processing $1.4 trillion in 2024. Adyen’s operating margin grows beautifully for years as their revenue grows, until they fully enter the U.S market, which required massive investment. Even with the investment, their operating margin is very very high: 44%.

I could have brought other companies in the space, Block, Shift4 or even more established names like PayPal and Fiserv. They all exhibit the same dynamics. As companies reach scale, first they achieve leverage on their COGS and next they achieve operating leverage on all the main expenses.

Scale brings benefits both on the cost and on the revenue side. It’s the holy grail of payments.

The pursuit of scale leads companies in the space to compete fiercely, despite a secular tailwind that's been growing the pie for all. This further leads to take rates dropping over time. There have been three approaches to augment organic growth to reach scale: M&A, vertical integration and horizontal geographic expansion in a race for coverage.

M&A to reach scale

Leading firms have pursued scale through both growth and consolidation. Recent years saw a wave of mega-mergers in the space. For example, Fidelity Information Services (FIS) acquired Worldpay in 2019 for $43 billion (including debt) , and Fiserv merged with First Data in a $22 billion deal. Justifying both deals executives explicitly argued that “scale matters in our rapidly changing industry” – bigger players can invest more in technology and offer more competitive pricing. While massive mergers don't quite always work out, scale is clearly a driver. In fact, FIS recently agreed to spin out Worldpay to Global Payments, each selling a respective business unit to the tother. Global Payments gave their issuing unit to FIS and FIS gave their merchant acquiring unit, Worldpay, to Global Payments. When discussing the transaction Global Payments said:

"We have identified compelling synergies enabled by substantial revenue enhancement and expense reduction opportunities as we benefit from our expanded suite of capabilities and solutions and greater economies of scale...."

"being a scale player in this industry matters more than ever, given the increasingly dynamic environment in which we operate. And with Worldpay, we add significant strength and expertise in key fast-growth areas of payments that complement our existing business while further enhancing our offerings with SMBs."

M&A also exists on smaller scales to jump start a business or region, or achieve synergies faster. This explains acquisitions like dLocal acquiring AMA, an African payment processing company in June of 2025, Rapyd acquiring PayU global's payment processing segment in LATAM and Africa. The need to reach scale and realize economies of scale justify an intense M&A pace in the space.

Vertical integration

Another way to achieve scale and differentiation simultaneously is vertical integration – controlling more parts of the payments value chain in-house. Block acquiring Afterpay to integrate BNPL is a clear approach to vertical integration. Adyen is also a prime example. The Dutch payments provider not only built a global processing platform, but also obtained its own banking licenses and acquiring capabilities to become a one-stop shop. Unusually for a fintech, Adyen is a licensed acquirer and direct card network member, effectively acting as its own sponsor bank. This lets Adyen cut out middlemen and extra fees – it can connect directly to Visa, Mastercard and local schemes, handling authorization, clearing, and settlement itself. The benefits are significant: Adyen can fine-tune how transactions are routed and retried, improving approval rates for merchants, and can implement network updates or new features on its own schedule. It also means Adyen keeps the full economics of the transaction, rather than sharing with partner banks.

Controlling more parts of the value chain don't only improve costs but improve the value being delivered. By having more access to data, Adyen can improve both fraud rates and acceptance rates of payments. Adyen hasn't only vertically integrated into the software parts of the stack, they've also become an omni channel commerce player - offering both hardware PoS terminals and software only solutions.

Adyen isn’t alone in their vertical integration strategy. PayPal is also doubling down on touching customers everywhere along the stack, including omni channel. They recently launched payment terminals in Germany.

Stripe won’t be left behind either. They’ve pursued partnerships and licenses (including an EU e-money license) to get closer to a similar model as Adyen, and has built out services like issuing, treasury, and recently also becoming a merchant of record to help companies deal with tax. Stripe has also recently acquired Bridge, a provider of stablecoin infrastructure and Privy, a smart contract wallet developer, to help improve cross border payment flow and enable further banking services for customers across the world.

Even Shift4, a smaller competitor, acquired Finaro in 2023 to give them access to vertical integration in new markets - in this case the EU.

Vertical integration across the business and payments stack helps payment companies cost costs and increase GMV.

Horizontal growth - geographic expansion

The 'global south', as in emerging markets, are regions of the world where fintech has seen an immense uptick, and as these economies are still in growth mode, promise a growing growth opportunity. It’s estimated to be ~$1.4 trillion GMV market.

It's no wonder that companies have looked to penetrate these markets and grow their GMV. However, growing globally, especially in emerging markets isn't easily done.

In a section above I addressed the key challenges of going global. It’s NOT as simple as turning a dial. Even the best operators in the space like Adyen, who are used to working across multiple markets think twice before entering true emerging markets. Pedro Arnt, the CEO of emerging market payment processor dLocal addressed this point on a recent podcast. Emerging markets are about horizontal expansion, not vertical integration:

Pedro Arnt: And so you could say, yeah, go offer them Germany, Sweden and Canada. And we've always said absolutely not. And the reason for that is although it sounds counter intuitive, there actually are significant similarities across the emerging world when you look at financial infrastructure.

So the key Success Factors of how you build, you don't build a vertically integrated stack like Stripe has or Adyen has because it's too fragmented. So you have to build a horizontal stack that optimizes what your merchants connect into.

But underneath it's extremely fragmented and complex. So we're more about this kind of technology build and almost like a middleware than we are vertical. And I think it would be impossible to try to be vertical across 40 plus subscale market.

You're not going to build 40 acquirers across small countries. And then when you begin to realize that, you say, hey, there's a lot more in common across these over 40 emerging markets that I serve, although some of them are literally on the other side of the globe.

The fragmentation, the early days of digital transition, the complexities around currency, the complexities around regulation.And what you realize is that if you were successful in LATAM, your company in many aspects has a lot of intrinsic DNA that ports really well to these other parts of the world.

Whereas in the EU, Adyen could integrate into Visa and Mastercard networks, become a merchant acquirer and achieve all the relevant money transmitting and banking licenses, this just doesn’t make sense in subscale emerging markets. While the global south is growing, these are still markets that are tiny compared to the developed markets - therefore they can’t justify the same amount of investment.

Here’s an example I like to show, the amount of payment options an emerging market pure play like dLocal offers vs Adyen. dLocal offers many more options than even a well established excellent competitor like Adyen.

While specializing in all emerging markets simply isn’t feasible, there are still many attractive parts of emerging markets and they still offer a lot of growth. Which is why many payment processors have recently entered and refocused on some of the most attractive and larger markets: Mexico, Brazil and India. Adyen and Worldpay have been active in Brazil for years, but they are increasingly focusing on growing the amount of payment methods they accept. New entrants like Shift4 and Fiserv’s Clover are launching as well. Rapyd, a ‘fintech as a service’ company purchased PayU’s Global Payment Organization, which gave Rapyd an on-the-ground presence across LatAm, Africa, and parts of Asia.

Payments summary and future trends

Let's try and bring all the different threads together so that we can create a coherent picture of the payments industry.

Payments processing has undergone a few disruptive changes over the past three decades. It's gone from an in-store location run by a few mega companies like First Data and Worldpay to an industry that's being eaten on the low end by vertical SaaS platforms and the embedded finance trend as the core technology is commoditized. From the e-commerce it’s been disrupted by new companies like Stripe and Adyen who have dominated those new verticals and the value services around it. The industry is now being reshaped. Not only across those two axes but also across the globe.

We saw how reaching scale is the most dominant factor in these companies' success so that they can generate operating leverage both on the cost side as well as on the operational cost side. To reach scale, anything goes: M&A, vertical and horizontal integration across different markets and even growth at all costs. If you can't reach scale, the odds are that you're either going to be gobbled up or stay very small. This is a cutthroat competitive industry because of the scale imperative and because of the low switching costs between payment providers. Large merchants by definition almost always work with multiple payment providers.

Thinking ahead, what are the key trends that we should be focusing on?

Value-added services are becoming more critical than ever. As embedded finance becomes more and more embedded across more verticals and platforms, the core parts of payments has been increasingly commoditized and the software stack around it becomes increasingly important. This is true for vertical SaaS offerings like Toast as well as for companies like Adyen and Stripe who are looking to offer everything from improved risk analysis and conversion to banking as a service.

A tapering of the secular growth trend will mean that legacy players should continue to struggle. Competition will increase and this will lead to increased M&A as companies with tons of free cash flow look to get out of their slump.

Increased global competition: Developed markets are reaching saturation. The global south remains a blue ocean. We should see more and more players enter the larger markets: Brazil, Mexico, India etc and partner for the longer tail markets.

We should see consolidation amongst the e-commerce players occur over time as well, much like we saw this occur in traditional payments. This is a scale business and we should expect this scale to continue in this part of the business as well.

Thoughts on companies in the space

Now, with some perspective under our belts, let's round this article out with some brief thoughts on a few names that I've researched as part of my exploration down the payments rabbit hole.

Adyen: ~$1.4T in TPV. the poster child and best of breed in the payments processing space, Adyen started off with helping enterprise clients in the complex European market. One API marked it beautifully, and has since expanded into the harder market of the United States. It's harder simply because it's simpler, and other companies like Stripe and PayPal were there first. This is one of the reasons why Adyen struggled in 2023 with lower margins, as they discovered that their amazing product in Europe isn't quite as revolutionary in the single simple market of the United States. However, what makes Adyen best in breed is their ability to surmount this and offer real value to customers, including ones in the U.S. And it's quite a show watching them take Stripe head-on and do a pretty good job of it. I’d love to buy Adyen on any significant pullback.

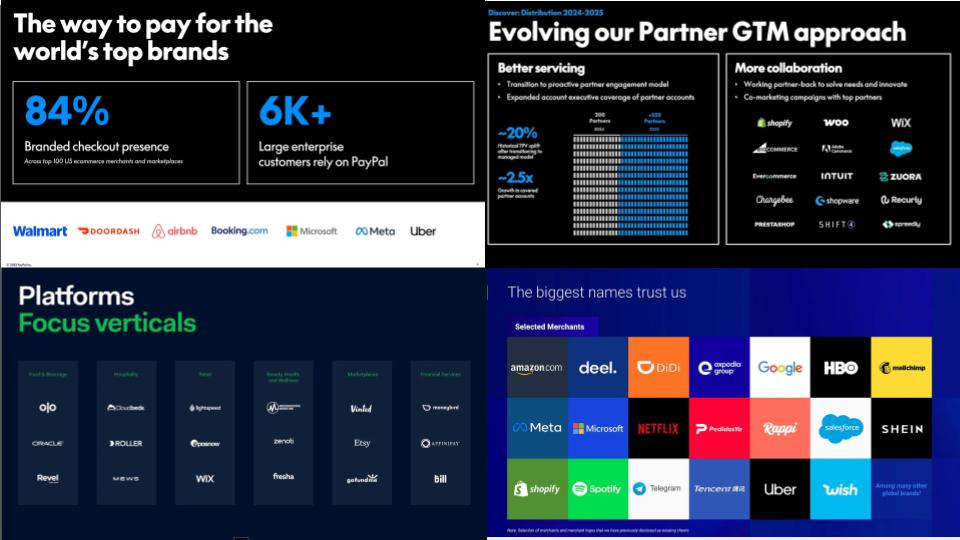

PayPal: ~$1.7T in TPV. PayPal feels to me like the Craigslist of payments. Every innovation in the space they did first, but never quite good enough. And most of the payments industry is simply unbundling some part of PayPal's offering.

It's amazing to think that PayPal did e-commerce online check out remittance and accounts receivables and payables for small businesses before any of the other companies on this list were even founded. However, part of that is what's caused them to slow. PayPal has a legacy infrastructure. So much so that rolling out their new unified checkouts across the world is a 3-year effort to simplify payments.

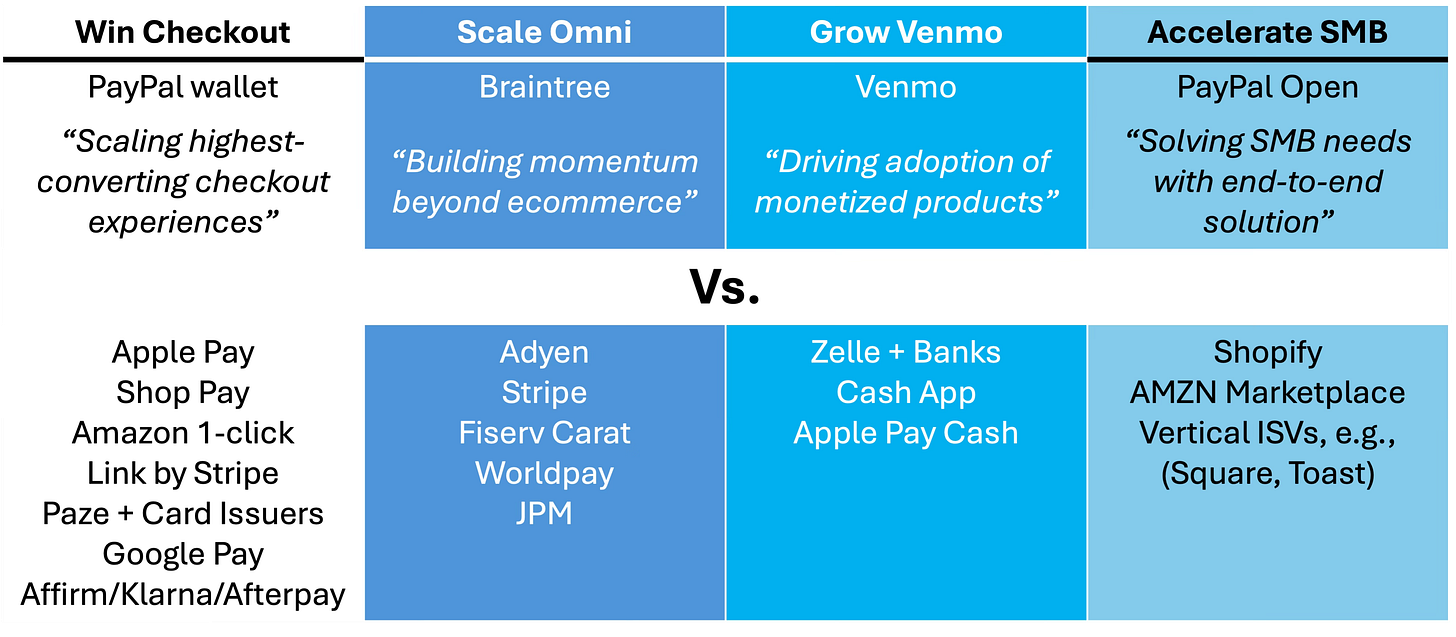

They've been outflanked on almost every part of their stack. Stripe is easier to integrate for developers, Adyen offers something more comprehensive for enterprise, Remitly offers a much better user experience for remittances, Payoneer offers small and medium business payments, a complete platform that's more user-friendly and comprehensive than what PayPal has to offer, and consumers use Cash App, Apple Pay, and Zelle just as much as they use Venmo. PayPal is in the middle of a strategic realignment where they've recognized that their key strategic advantage is being able to close the loop between consumers and merchants. They're the only payment processor beyond Square who have both an end-to-end touch point with consumers in the form of Venmo and payment processing and checkout offerings to merchants. If they could bridge that gap, they could generate real value add to merchants. However, I'm very skeptical that they will succeed.

PayPal’s products vs the competition. Source Stripe: ~$1.4T in TPV. Stripe has been the darling of Silicon Valley for years, and it looks like they've earned that status having grown at a meteoric rate over a decade to $1.4T in TPV, that is an astounding compound annual growth rate. They were also the first to market with a low-end solution where developers with 7 lines of code can integrate a full payment stack, and they haven't stopped pushing the envelope since, neither on quick checkouts nor with a full suite of vertical integration all the way up the banking value chain. It's a shame that Stripe is in public and so metrics are very hard to come by, but in terms of products, this is a very interesting company to follow.

dLocal: ~$27B in TPV. because of the company DNA and running lean, as well as higher take rates that exist in emerging markets. I'd best describe Dlocal as a startup going through growth pains. They've had their challenges in the public markets, but with a new and very experienced CEO at the helm, there's lots of blue ocean ahead. I'll have a more in-depth article on D-Local specifically, but suffice it to say that they've built very impressively a small-scale payments processor in emerging markets that is profitable, which is quite a different feat than all of their developed markets' competitors. It's probably both. If they can survive the incoming competition into their key markets.

Shift4: ~$176 in TPV. Shift4 sits in an interesting position because it’s in the middle of everything. Shift4 plays in the hospitality space similar to other vertical SaaS companies, Toast, Lightspeed and Block. On the other hand it’s now a full on competitor to Adyen in their Unified Commerce segment. They’ve also grown considerably especially through M&A. Shift4 have executed very well over their public company history but don’t quite get the credit that other vertical platforms like Toast get. This is most likely due to a higher debt load and their M&A based strategy, over the organic growth that Toast enjoys. They’re a serious competitor in any event.

Fiserv: ~$2T in TPV. Fiserv is a legacy player, who is arguably the best in class legacy player. This is due to both their size, execution and ability to innovate in both segments coming under pressure: e-commerce and vertical SaaS. Fiserv’s Clover is a good competitor in the vertical SaaS space, arguably the only legacy player to have a strong vertical SaaS offering for the SMB space. Carat is their global e-commerce offering that competes with the Adyen’s of the world. I’ve covered Fiserv more here.

Global Payments: ~$3.7T TPV. Global Payments is a legacy player that’s struggled to stand out. On the low end, it has a scattered mix of small brands with no clear winner or unified strategy. On the high end, it lacks a differentiated enterprise offering and strong brand presence. Despite this, the business generates ~$2.8B in free cash flow from $10 billion in revenue—showing the power of scale and operating leverage.

The company is now trying to reset. It’s divesting its issuing unit to FIS and acquiring Worldpay in return, giving it more exposure to e-commerce and acquiring. At the same time, it’s rebranding its low-end portfolio under a single product called Genius to compete with Clover. If it executes, this could mark a turning point, but the jury’s still out, and the competition is tough.

Payoneer: ~$80B TPV. Payoneer is one of the companies I consider to be unbundling PayPal. They provide a platform that serves both SMBs and other platforms. It’s essentially a “banking” and payments-as-a-service offering—handling accounts payable, receivable, and cross-border transactions. For platforms, it also supports payouts to creators. Increasingly, they’re carving out a position in the B2B payments space, including remittances and international flows.

Remitly: ~$60B TPV. another company unbundling PayPal, and this is one of PayPal's core use cases: sending person-to-person payments globally. However, the fees were too high and the user experience too low, which gave the opportunity to companies like Remitly to build an end-to-end consumer-facing platform that deals with remittances and p2p payments. They have an outstanding consumer rating and now handle cross-border payments in over 150 countries. Who manages their payments on the back-end is the key question. But here, as well, as they reach scale, they gain the benefits of being able to net out inflows and outflows from specific markets.

Square: ~$231B TPV. Square is the OG of vertical SaaS, and while the company has floundered recently, they deserve a spot in the Hall of Fame of disruption. As I mentioned above, they disrupted traditional merchant acquiring on several different categories and opened the door for a host of newcomers. Today they are trying to refocus both in the hospitality segment where they have been outcompeted by the likes of Toast and Shift4, and they have been focusing a lot on Cash App, their P2P payments application, and cryptocurrency, specifically Bitcoin mining. It's unclear whether shifting into Bitcoin mining will be a net positive for the company, but I believe it's an unnecessary distraction.

Toast: ~$160B TPV. Toast is the leading vertical SaaS company in the hospitality space. And as that, it deserves a special place of honor in the Payments Roundup. It's the quintessential example of embedded finance and payments in a vertical SaaS company. Toast offers a host of software solutions specifically for restaurants and as such also a point-of-sale solution that is hardware and software integrated. You don't have to use Toast's payment processing. You could use a different merchant acquirer, but having the bundle makes it much easier. On top of the payment processing, they also offer other embedded finance offerings like Toast Capital, which offers small loans to restaurants. At its current GMV, Toast is no longer a small payments processor, but taking an ever-increasing part of the payment processing pie.

JPM Payments: ~$2. trillion in TPV. Payments aren’t complete without an honorable mention of JPM, who are the largest payment processor in the world (when including banking services). However they don’t break out this segment on a regular basis and payments are overall a small part of their overall revenue.

Thanks for reading!

This is excellent!

Thank you very much for your input, I learned a lot.

Thank you!